Morgowr and the History of Sea Monsters in Cornwall

- Rob Vickery

- Jan 25

- 11 min read

A cultural and historical examination of Cornwall’s long relationship with sea monster sightings, belief, and the legend of Morgowr.

Cornwall and the Sea

Its relationship with the sea has always shaped Cornwall. For centuries, coastal life revolved around fishing, trade, and navigation, with communities depending on the water for survival while fully aware of its dangers. Boats left harbours knowing they might not return. Storms arrived without warning. Reefs and tides claimed vessels regularly. Along the Cornish coast, wrecks became so common that they were part of local knowledge rather than rare events. This closeness to danger created a culture where the sea was not just a workplace but a force with its own moods and intentions.

Fishing villages grew in sheltered coves where access to the water was everything. Families were tied to the sea through daily labour. Men worked on trawlers and luggers. Women processed fish on the quay. Children grew up learning tides and weather as naturally as reading. When livelihoods depend on forces beyond human control, belief systems grow around them. In Cornwall, this took the form of spirits, warnings, and stories passed quietly through families and openly through pubs and harbours.

Among these beliefs were figures such as the Bucca, a shapeshifting being said to live in caves and offshore waters. Sometimes helpful, sometimes destructive, the Bucca reflected the unpredictable nature of the sea itself. Mermaids also appeared in local tradition, often less romantic than later popular culture suggests. They were warnings as much as wonders, linked to shipwrecks and drownings. These ideas were not fringe fantasies. They were part of how communities explained loss and danger in an era with little scientific certainty.

Against this backdrop, it is not surprising that accounts of strange creatures at sea were taken seriously. When fishermen reported something unusual, it was weighed against experience rather than dismissed outright. This cultural setting forms the foundation for understanding why sea monster reports found fertile ground in Cornwall long before the name Morgowr ever appeared.

Victorian Era Sightings and Early Reports

The first widely recorded Cornish sea monster accounts entered the public record during the Victorian period, when expanding newspapers connected regional stories to a national audience. In January 1877, the West Briton printed a report reprinted from the Birmingham Post concerning Captain Drevar of the ship Pauline. Drevar claimed to have seen a sea serpent on three separate occasions. According to his account, the creature followed his vessel and appeared to catch and crush whales within its coils.

What made this report notable was not its dramatic description but the source. Drevar was not a casual observer or a landsman unfamiliar with marine life. He was a working sea captain whose livelihood depended on accurate judgement of what he saw on the water. Victorian readers understood this distinction. The press often emphasised professional status when reporting sightings, suggesting an early awareness that credibility mattered.

Such reports were rarely treated as settled fact, but neither were they automatically dismissed. Editors framed them with caution while allowing readers to draw their own conclusions. In coastal towns, these stories circulated far beyond the printed page. Fishermen discussed them in relation to their own experiences, comparing descriptions with known animals and unusual encounters they had witnessed themselves.

Another important account came in September 1903. Captain White of the Falmouth tug Triton was returning from Dublin when he spotted something unusual roughly fifteen miles from Longships lighthouse. White described a serpent around one hundred feet long, moving at remarkable speed. Its head was unlike anything he recognised and was said to possess tusks several feet in length. White had spent thirty years sailing between Falmouth and the Isles of Scilly and openly admitted he could not explain what he saw.

This admission is significant. White did not claim certainty or sensational knowledge. Instead, he emphasised his confusion. That uncertainty is a recurring feature in many serious sea monster reports. Witnesses often describe their own limits of understanding rather than asserting definite conclusions.

In August 1906, another high-profile sighting occurred when the liner St Andrew passed Land’s End while en route from Antwerp to New York. Two officers and a passenger reported seeing what they described as a wonderful sea serpent. They observed five or six yards of its body rising clear of the water, jaws visible and lined with large teeth. The sighting lasted nearly a minute before the creature submerged. Again, the account came from multiple witnesses who had ample time to observe the object rather than a fleeting glimpse.

Newspapers reported these sightings with a mixture of fascination and scepticism. They were presented as curious rather than conclusive. Nevertheless, they were widely read. In Cornish pubs, such accounts were discussed alongside weather, catches, and shipping news. They entered local conversation as possibilities rather than fantasies.

Interwar Sightings and Working Coastlines

The early twentieth century brought further reports, particularly during the interwar years when fishing remained central to Cornish life. In May 1926, two fishermen, Rees and Gilbert, were trawling near Falmouth when their net became impossibly heavy. They spent more than an hour hauling it in. When it finally surfaced, they found among the fish a creature around twenty feet long.

Their description was detailed and unsettling. The animal was said to have a beak around two feet long, four legs covered in scales that appeared joined like armour, a back matted with brown fur, and a thick tail extending eight feet. Unsure what to do, the fishermen hesitated. Before they could act, the creature forced itself overboard, leaving blood on the deck and clumps of fur behind. These tufts were taken ashore, but no explanation was ever offered by scientists at the time.

Whether misidentification, exaggeration, or something genuinely unusual, the account highlights an important pattern. Many sightings occurred during routine work rather than moments of excitement. Fishermen hauling nets had no incentive to invent danger. Their reactions tended toward confusion rather than triumph.

The 1930s produced a cluster of coastal sightings sometimes grouped under the informal label of the North Coast Nessie. In July 1934, four people sitting on Whitsand Bay beach observed a snake-headed creature swimming with an undulating motion described as caterpillar-like. The following year, off Port Isaac, a glossy black animal was reported on three occasions. Postman Mr Honey described a goose-like neck rising four feet above the water and a large barrel-shaped hump. He watched it for several minutes as it moved smoothly without leaving a wake.

In June 1935, at the River Gannel near Newquay, tea room owner R. Northey saw an animal estimated at twenty-five feet long moving quickly along the surface. He compared its motion to that of a submarine. These reports came from different individuals with no apparent connection, yet they shared recurring features such as long necks, humps, and smooth movement.

During this period, Cornwall still lived very close to the sea. Radio and cinema were present, but daily life remained grounded in physical labour and direct observation. Stories spread by word of mouth and were often retold cautiously rather than embellished wildly. For some listeners, these tales were entertaining. For others, they carried the weight of warning.

The Emergence of Morgowr

The modern chapter of the story began in the mid 1970's, a time when Cornwall itself was changing. Tourism was expanding rapidly. Traditional fishing industries were in decline. Coastal communities were adjusting to new economic realities. Into this moment, the creature later known as Morgawr emerged.

The name Morgowr comes from the Cornish language and translates roughly as 'sea giant'. It was a simple term that resonated locally and quickly stuck. In September 1975, Mrs Scott and Mr Riley reported seeing a humped creature with a bristled neck and short horn-like projections off Pendennis Point. They stated they watched it catch a conger eel. The sighting was unusual enough to attract attention but did not yet spark widespread interest.

That changed in March 1976 when the Falmouth Packet published two grainy photographs sent anonymously by a woman identified only as Mary F. The images were taken from Trefusis Point near Flushing and showed a dark shape in the water with what appeared to be humps and a raised neck. Alongside the photographs was a letter in which Mary F described seeing something like an elephant waving its trunk, except the trunk was a long neck with a small head. She wrote that the animal frightened her and that she would not want to see it any closer.

Mary F never revealed her identity publicly. This anonymity added to the mystery rather than undermining it. The photographs were unclear but suggestive. They offered just enough detail to encourage interpretation without providing firm answers. Fishermen began joking and complaining that Morgowr was responsible for poor catches. Local headlines followed. The Helford River was soon nicknamed Morgowr’s Mile.

Bones on the Beach and Physical Evidence

Almost simultaneously, another story emerged, one involving physical remains rather than photographs. In January 1976, Mrs Kaye Payne of Falmouth discovered the carcass of a strange animal washed up on Durgan Beach. Some immediately speculated that Morgawr had died and come ashore. Before scientists could examine it, the tide reclaimed the body.

Shortly after, a thirteen-year-old boy named Toby Benham came forward. A keen naturalist from Mawnan Smith, Benham explained that weeks earlier, he had found a skeleton roughly ten feet long on nearby Prisk Beach and had taken the skull home. When he saw a photograph of Mrs Payne holding a bone, he recognised it. Benham stated confidently that the skull was from a whale.

Later examination by cryptozoologists Jonathan Downes and Darren Naish confirmed his assessment. The skull was identified as belonging to a pilot whale, either Globicephala melas or possibly Globicephala macrorhynchus, with features pointing toward the long-finned species. The skull itself became an object with a strange afterlife, serving at various times as a garden doorstop and an art prop before eventually entering the CFZ Museum.

Despite the explanation, for a time locals referred to it as the Durgan Dragon. This episode demonstrates how quickly physical evidence can be absorbed into folklore when uncertainty and expectation combine. Even a whale skull could become proof of a monster under the right conditions.

Witnesses and Personal Testimony

As the Morgawr story developed, eyewitness accounts multiplied. Duncan Viner, a dental technician from Truro, reported seeing a creature around thirty feet long off Rosemullion Head. He initially assumed it was a whale until it raised a long neck from the water. On Good Friday 1976, a Helston schoolboy described a weird animal with two humps and a snake-like neck in the Helford River near Toll Point. Holidaymakers Allan and Sally White reported a similar sighting off Grebe Beach.

One particularly notable account came from Donald Ferris, a council worker from Falmouth who had previously dismissed Morgowr as a joke. While walking his dog on Gyllyngvase beach in September 1976, he saw what he thought was a small boat approaching. As it drew nearer, he realised it was a grey eel-like creature estimated at sixty feet long. Ferris later stated that the experience shook him deeply and changed his view entirely.

The most famous Morgowr encounter involved fisherman George Vinnecombe. In July 1976, Vinnecombe and his friend John Cock were out on calm water when they spotted what they believed was a capsized boat. As they approached, a head rose on a neck approximately six feet long. Vinnecombe later stated that the creature was as large as their thirty-two-foot boat. Both men were experienced fishermen familiar with whales and dolphins and insisted this was something different.

An official from the Natural History Museum interviewed the men separately. Their sketches closely matched. When shown illustrations, both identified a plesiosaur as the closest match. The official suggested a turtle. Vinnecombe rejected this explanation, stating that after forty years at sea, he knew what he had seen.

Morgawr in Popular Culture and Media

By the late nineteen seventies Morgowr had become a cultural phenomenon. Television programmes such as ITV’s Strange but True later revisited the story. Local schools held competitions where children designed Morgowr costumes. In pubs around Falmouth stories grew with each retelling. The creature moved from uncertain sighting to shared reference point.

A key figure during this period was Tony Doc Shiels, a local artist and magician. Shiels claimed he could summon Morgawr using psychic powers and staged rituals along the Helford. His involvement attracted national media attention and blurred the boundary between belief, performance, and provocation. Witches arrived claiming they would swim naked to lure the creature. Reporters followed. The spectacle complicated public perception of Morgowr, introducing deliberate theatre into an already ambiguous narrative.

This mixture of genuine witness testimony and overt showmanship made it increasingly difficult to separate sincere belief from playful exaggeration. Yet it also ensured that Morgowr became embedded in Cornwall’s modern identity. The creature was no longer simply something in the water. It had become a story people recognised and responded to.

Scientific and Cryptozoological Explanations

Attempts to explain Morgowr and earlier sea monster sightings have taken many forms. One long standing theory proposes that such creatures are surviving plesiosaurs. Supporters point to the recurring silhouette of a long neck and small head rising above humps. Critics counter that no confirmed plesiosaur remains have ever been found in modern waters. Proponents respond by suggesting that plesiosaurs swallowed stones for ballast, meaning their bodies would sink rather than wash ashore.

Another influential approach emerged in the nineteen sixties with the work of Bernard Heuvelmans, often referred to as the father of cryptozoology. In his book Le Grand Serpent de Mer published in 1965, Heuvelmans argued that there was no single sea serpent but multiple types. Among them he proposed a long necked seal which he named Megalotaria longicollis. He believed this explained many periscope like sightings more convincingly than reptilian survivors.

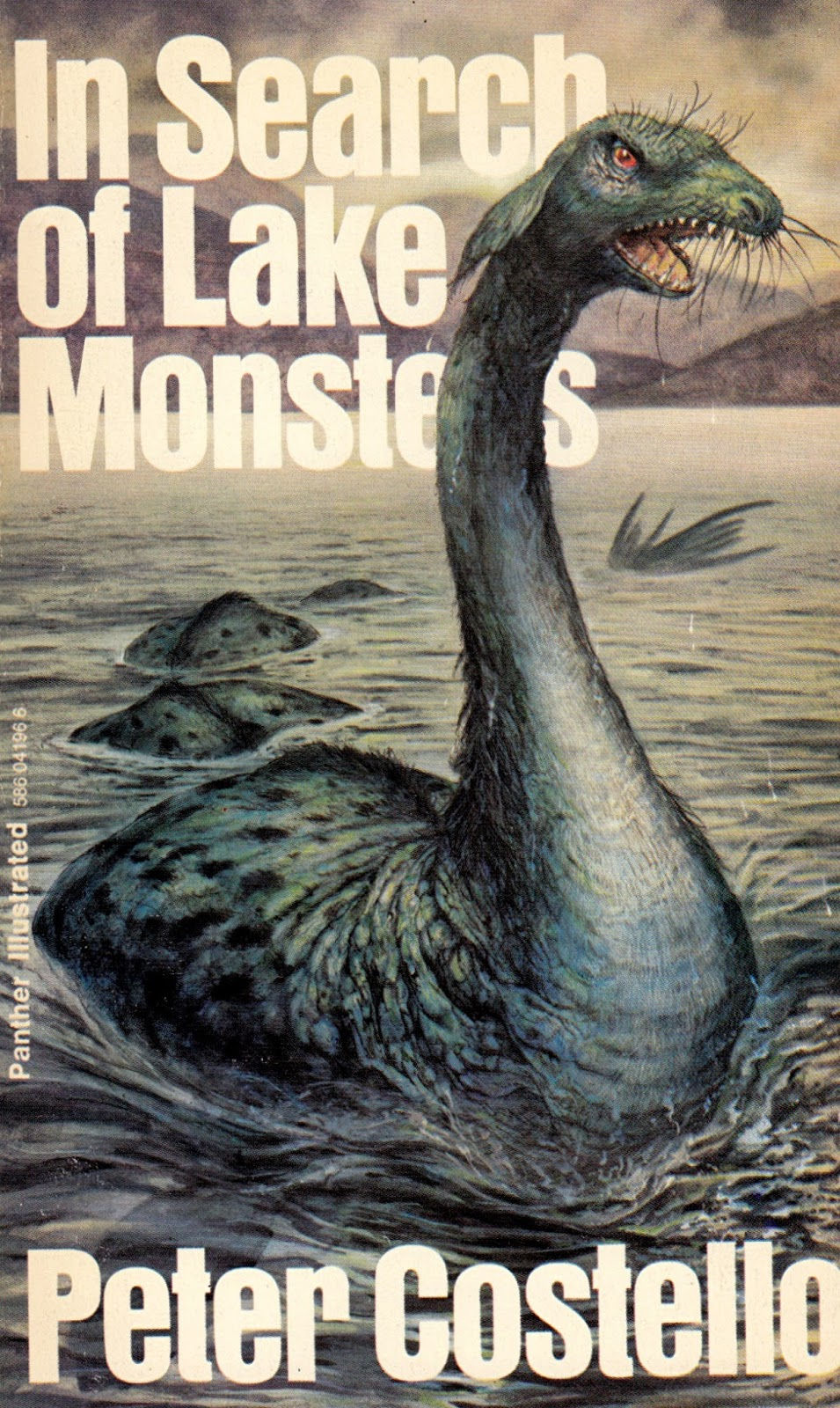

Peter Costello later expanded this idea in his 1974 book In Search of Lake Monsters, suggesting that lake monsters such as Nessie were also long necked seals adapted to freshwater environments. He described them as sonar hunters with sharp hearing and vocalisations similar to sea lions. This theory appealed to those seeking a biological explanation without invoking extinct reptiles.

The long necked seal hypothesis raises challenges. Only a small number of seal species live in freshwater today, such as the Saimaa and Ladoga ringed seals and isolated common seal populations in Alaska and Quebec. The idea that a large unknown seal species could exist undetected across multiple regions remains contentious. Nonetheless the theory remains influential due to its relative plausibility.

The Orkney Case and the Long Necked Seal Hypothesis

One of the strongest cases supporting the long necked seal idea comes from the Orkneys rather than Cornwall. In 1919 J Mackintosh Bell, a lawyer on holiday, was rowing with fishermen in the Pentland Firth when a creature they often spoke of appeared. Bell described a rough skinned neck as thick as an elephant’s leg rising six feet above the water, topped with a dog like head and whiskers. When it dived, Bell observed it swimming alongside the boat with paddles visible. His sketches resemble a seal with an unusually long neck.

If accurate, Bell’s account represents one of the most compelling examples of a creature that fits neither known seal species nor extinct reptiles neatly. It continues to be cited by cryptozoologists as evidence that something unusual may exist or have existed.

What Morgowr Represents

Returning to Cornwall, the Morgowr story draws together many of these threads. From Victorian captains reporting serpents at sea, to fishermen hauling something unknown into their nets, to modern witnesses describing long necked creatures in familiar waters, the pattern remains consistent. Each generation names the phenomenon differently, but the underlying experience persists.

Whether Morgowr represents misidentified wildlife, an undiscovered species, a product of cultural expectation, or a combination of all three remains unresolved. What is clear is that the legend itself has become part of Cornwall. Like wrecks, mermaids, and the Bucca, Morgawr reflects how people relate to a powerful and unpredictable environment.

The sea has always produced uncertainty. Morgowr gives that uncertainty a shape. Not a definitive answer, but a shared reference point for things seen and not fully understood. In that sense, the creature’s endurance says as much about human perception as it does about what may or may not move beneath the surface.

Comments